First implant to restore sight

Trial participant, Sheila Irvine, being trained

The results of a pivotal European clinical trial of a new electronic eye implant have been shared today (20 October).

The study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed 84 per cent of participants were able to read letters, numbers and words using prosthetic vision through an eye that had previously lost its sight due to the untreatable progressive eye condition, geographic atrophy with dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD). They could also read, on average, five lines of a vision chart; some participants could not even see the chart before their surgery.

The trial, with 38 patients in 17 sites across five countries, involved the PRIMA device, Moorfields being the sole UK site. All participants had lost the central sight of the eye being tested, leaving only limited peripheral vision.

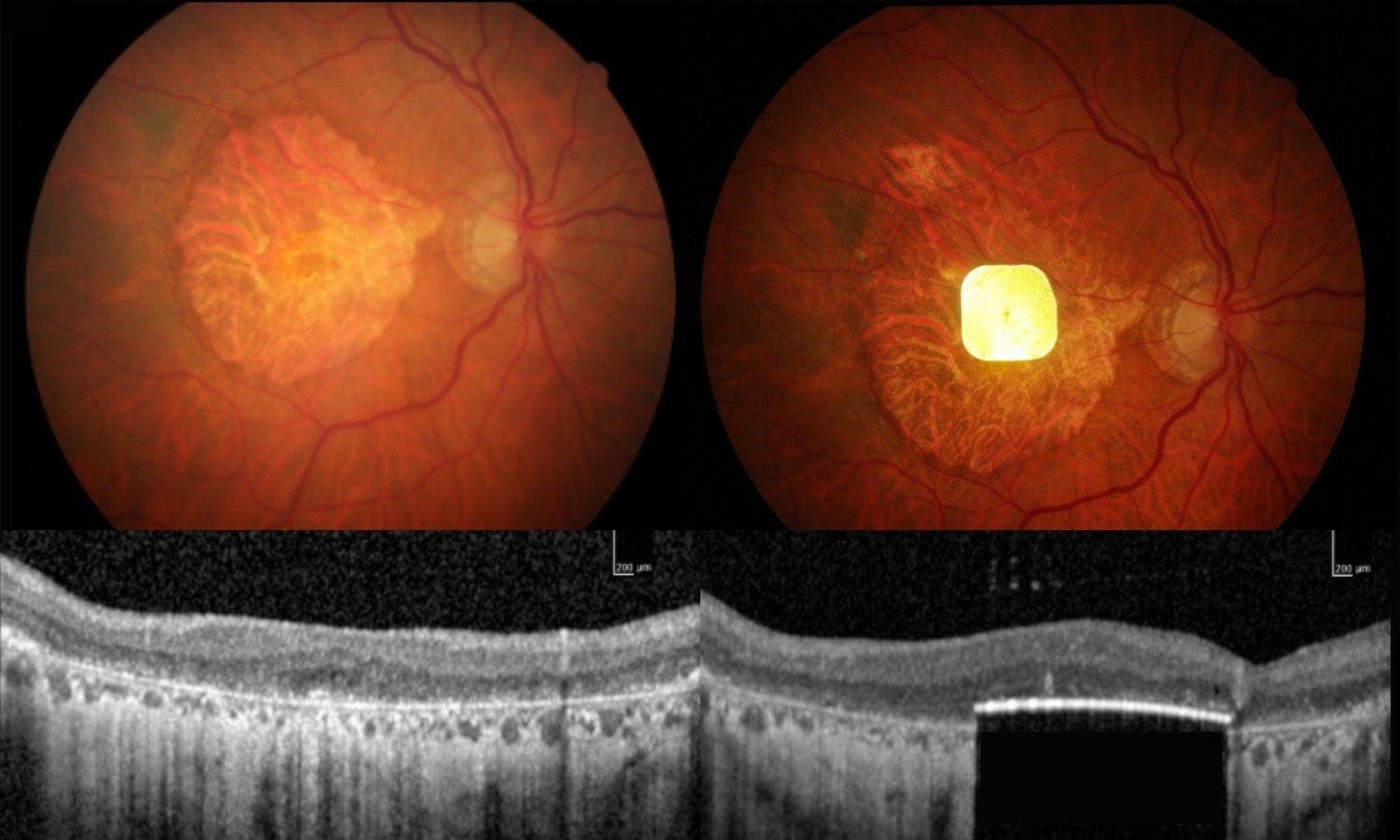

The new implant is the first ever device to enable people to read letters, numbers and words through an eye that had lost its sight. The procedure involves a vitrectomy, where the eye’s vitreous jelly is removed, and the surgeon inserts the ultra-thin microchip, which is shaped like a SIM card and just 2mm x 2mm. This is inserted under the centre of a patient’s retina, by creating a trapdoor into which the chip is posted.

The patient uses augmented-reality glasses, containing a video camera that is connected to a small computer, with a zoom feature, attached to their waistband. Around a month or so after the operation, once the eye has settled, the new chip is activated. The video camera in the glasses projects the visual scene as an infra-red beam directly across the chip to activate the device. Artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms through the pocket computer process this information, which is then converted into an electrical signal.

The implant in the eye (right)

This signal passes through the retinal and optical nerve cells into the brain, where it is interpreted as vision. The patient uses their glasses to focus and scan across the main object in the projected image from the video camera, using the zoom feature to enlarge the text.

Each patient goes through an intensive rehabilitation programme over several months to learn to interpret these signals and start reading again. No significant decline in existing peripheral vision was observed in trial participants.

These findings pave the way for seeking approval to market this new device.

Sheila Irvine, one of Moorfields’ patients on the trial, said: “I wanted to take part in research to help future generations, and my optician suggested I get in touch with Moorfields. Before receiving the implant, it was like having two black discs in my eyes, with the outside distorted.

“There was no pain during the operation, but you’re still aware of what’s happening. It’s a new way of looking through your eyes, and it was dead exciting when I began seeing a letter. It’s not simple, learning to read again, but the more hours I put in, the more I pick up.”

Mahi Muqit, senior vitreoretinal consultant at Moorfields Eye Hospital and the Institute of Ophthalmology at UCL, added: “In the history of artificial vision, this represents a new era. Blind patients are actually able to have meaningful central vision restoration, which has never been done before.

“Getting back the ability to read is a major improvement in their quality of life, lifts their mood and helps to restore their confidence and independence. The PRIMA chip operation can safely be performed by any trained vitreoretinal surgeon in under two hours – that is key for allowing all blind patients to have access to this new medical therapy for GA in dry AMD.”

Read more about this story on the Moorfields Eye Hospital website.