What is keratoconus?

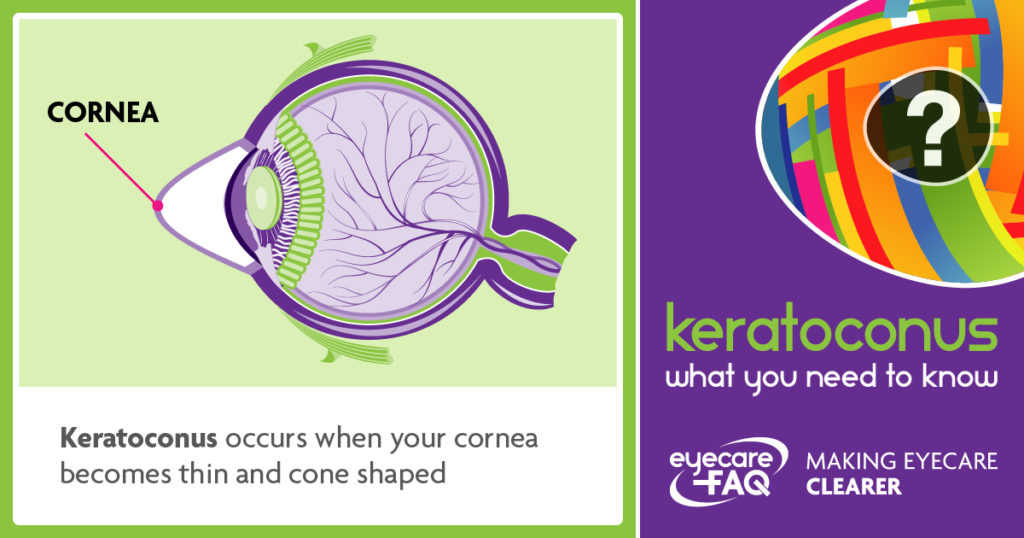

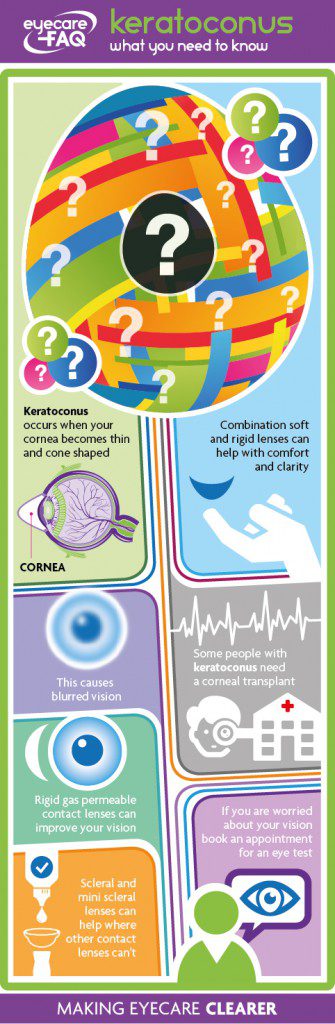

Keratoconus happens when your cornea, the clear layer at the front of your eye, becomes weaker and thinner in the centre. The thinning causes it to bulge outwards in an irregular cone shape. This type of focusing problem is known as “irregular astigmatism”. The cornea should be clear and regular to focus light. The change in shape means that your vision can become distorted and blurred.

Who gets keratoconus?

People usually develop keratoconus usually develops in their teens or 20s. It can worsen over time. It usually affects both eyes but may be worse in one eye than the other. About 1 in 2000 people develop keratoconus. It affects men and women equally. It may be more common in certain ethnic groups, for example, keratoconus affects about 1 in 450 South Asian people.

It’s not entirely clear what causes keratoconus. For around 10-14 percent of those with the condition it runs in the family. People who have allergies may be more likely to develop keratoconus. Some research seems to suggest certain people have fewer of the fibres that make a cornea strong, others may not be as good at healing. It has been suggested over a number of years that eye rubbing is implicated in its development, proven or not it would seem a good idea to avoid doing this.

What are the signs of keratoconus?

Many people have a small degree of astigmatism, where the front of the eye is rugby shaped rather than round. This can be corrected by a lens which is cut in a complementing shape. Keratoconus causes your cornea to develop an irregular shape, leading to irregular astigmatism. This is hard to correct with spectacle lenses, so one of the first signs of keratoconus can be increasing astigmatism and blurred vision despite spectacle correction. A contact lens can provide a regular front surface to the eye, however, and improve vision.

People with keratoconus can also become short-sighted (myopic) – this means distant objects appear blurred.

The irregular shape of the cornea can also lead to dazzle and glare in bright light, halos round lights and difficulties with night vision.

How is keratoconus treated?

Keratoconus can’t be treated with eye drops or medication. At first, glasses can improve your vision. As the cornea becomes more irregular you may need contact lenses to provide a regular surface and good vision. There are different types of lenses which can help as your condition progresses, including soft contact lenses specially designed for keratoconus, rigid gas permeable corneal lenses and scleral lenses. A rigid lens can also be ‘piggy backed’ onto a soft lens to improve vision and comfort.

A treatment called collagen cross-linking has been developed to slow the development of keratoconus, there is an early window of opportunity for this treatment to be effective, and therefore early diagnosis is important. Some people can benefit from corneal implants which try to improve the shape of the cornea to give better vision with contact lenses.

If your keratoconus has reached a stage where contact lenses no longer give clear vision and/or there is scarring which blurs the vision, a corneal transplant can improve sight to a good level again.

Is keratoconus associated with other medical conditions?

People with eye conditions Leber’s congenital amaurosis and retinitis pigmentosa, as well as the genetic conditions osteogenesis imperfecta, Ehlers-Danlos, Marfan, Turner and Down’s syndromes can be more likely to develop Keratoconus. People with these conditions need regular eye tests although not all of them will develop keratoconus.

How is keratoconus diagnosed and monitored?

There is a combination of tests to diagnose keratoconus. Your specialist will also monitor changes to the shape of your cornea over time. Refraction checks the prescription that you will need to best correct your vision. Keratometry measures the curve of your cornea. Computerised corneal mapping (topography) can create an image of your cornea showing the areas which are most curved. Corneal pachymetry measures the thickness of your cornea. Young people don’t always recognise or report changes to vision, especially if it primarily occurs in one eye, so regular eye exams are important.

What can be done to slow the progression of keratoconus?

Collagen cross-linking is used to treat progressive keratoconus. It is thought that it works by increasing the number of naturally occurring collagen cross-links in the middle layer of your cornea, the stroma. An ophthalmologist or specialist nurse applies drops to your eyes, and then UVA light. It takes around 30-60 minutes and is a day treatment. Some people find it improves their vision. It is usually done on one eye at a time. This treatment is available on the NHS in some hospitals.

Corneal cross linking is a relatively new technique with a 90% success rate in stopping progression however it usually does not improve vision. It can be performed on one or two eyes depending on the signs of progression. It has not been performed on the same eye more than once and has not yet been assessed in the long term. It can be performed under a local or general anaesthetic and involves UVA light for 30 mins with Vitamin B2. For several weeks afterwards a combination of steroids, anti-inflammatories and artificial tears are prescribed. A contact lens may be fitted after 12 weeks when the keratometry readings are stable.

How does a corneal transplant help people with keratoconus?

For most people with keratoconus, contact lenses provide good vision. For some people, contact lenses can become very uncomfortable, or can only be worn for a very short time. Some people with keratoconus develop corneal scarring. In either of these cases the ophthalmologist may recommend a corneal transplant.

Your damaged cornea is removed and replaced with healthy, clear cornea tissue from the eye of a donor who has died. The whole cornea or certain layers of the cornea can be replaced. 10-25 percent of people with keratoconus need to have a corneal transplant. It can take months for your vision to reach its optimum level after a corneal transplant. Corneal transplants have a low risk of failure: 95 percent or more are still healthy 5 years after surgery. You may, however, need a number of transplants in your lifetime as 50 percent of grafts are no longer working at 20 years. This is why the ophthalmologist advises waiting as long as possible for a corneal transplant. The risk of rejection and failure goes up each time a transplant is done. Following a transplant you are likely to still need contact lenses. You will also need to use steroid eye drops for at least six months to prevent rejection of the new tissue. Your ophthalmologist will discuss when it is right for you to have a corneal transplant and which type of transplant may be the best one for you.

How do I find out more about keratoconus?

There is more information on keratoconus from Moorfields Hospital and from RNIB