Dry eye corner: Part 1

In Part 1 of our new Dry Eye Corner series, Keith Tempany examines the composition and functions of the tear film – and the influence of the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society on dry eye disease knowledge and management…

Before we can begin to focus on dry eye disease (DED), we must first examine the pre-corneal tear film, its complexity and its functions. Only then can we hope to understand the consequences of DED and its effects on our patients.

Composition of the tear film

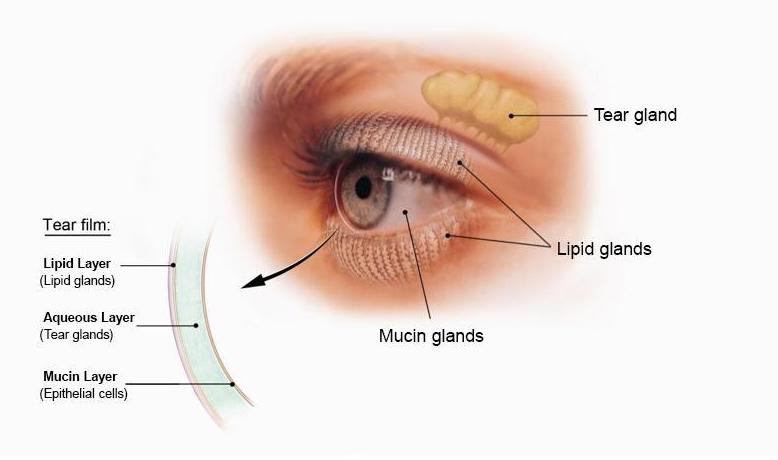

The three layers of the tear film work together to ensure the eye’s surface remains healthy and functional (image courtesy: US National Eye Institute)

The tear film is a thin, complex, multilayered fluid that covers the entire surface of the eye – and it is essential for maintaining ocular health, clear vision and comfort. The tear film is traditionally thought of as having three main layers: a lipid or oily layer; an aqueous or watery layer; and a mucin or mucous layer.

The three layers of the tear film work together to ensure the eye’s surface remains healthy and functional.

The base layer is the mucin layer. This innermost layer is produced by the goblet cells within the conjunctiva and the epithelial cells of the cornea and conjunctiva. It consists of glycoproteins that help the tear film adhere to the naturally hydrophobic corneal surface, making it wettable. I like to think of it as the ‘velcro’ of the tear film, holding everything in place. As I remind my patients, the tear film is vertical, but it doesn’t fall off, and this is why.

The aqueous layer is by far the thickest layer, making up about 80 per cent of the tear film, and is secreted by the lacrimal glands and accessory glands – termed Krause and Wolfring glands. It is primarily water (98 per cent) but also contains essential components like electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride and bicarbonate), proteins, growth factors and antimicrobial substances (lysozyme, lactoferrin and immunoglobins like IgA).

The outermost and thinnest layer is the lipid layer, secreted primarily by the meibomian glands in the eyelid margins, with minor contributions from the glands of Zeiss and Moll. It is composed of non-polar lipids like cholesterol esters and wax esters, which form a smooth surface at the eye-air interface.

Functions of the tear film

The tear film performs several vital functions for the eye:

- Maintains a smooth optical surface. By filling in minor irregularities on the corneal surface, the tear film creates a smooth refractive surface, which is crucial for the eye to focus light correctly and achieve clear vision

- Lubrication. The tear film lubricates the surface of the eye and the inner surface of the eyelids, preventing friction and damage to epithelial cells during blinking and eye movements

- Protection and defence. The aqueous layer contains enzymes and antibodies (like lysozyme and IgA) that destroy bacteria and prevent infection. The film also physically removes foreign bodies, debris and waste products from the eye through blinking and drainage via the tear ducts

- Nourishment and oxygen supply. The avascular cornea (which has no blood vessels) receives necessary oxygen and nutrients, such as electrolytes and glucose, from the aqueous layer of the tear film

Mechanism and dynamics of the tear film

The tear film mechanism is a continuous, dynamic process. The various glands (lacrimal, meibomian and goblet cells) constantly produce the components of the tear film. This process is regulated by neural and hormonal signals.

Blinking is essential for distributing the tear film uniformly across the ocular surface and reforming its layered structure. As the eyelids close, meibum is expressed, and as they open, the lipid layer spreads, drawing the underlying aqueous-mucin layer with it to create a smooth, refractive surface for clear vision.

Between blinks, the tear film gradually thins due to evaporation (retarded by the lipid layer) and drainage. Tears are moved toward the inner corner of the eye (medial canthus) and drain into the lacrimal puncta, passing through the canaliculi to the lacrimal sac and finally down the nasolacrimal duct into the nose, in a process known as the lacrimal pump mechanism.

Sensory nerves in the cornea detect changes, such as changes in the homeostasis of the tear film due to evaporation, which trigger reflex tearing (increased aqueous production) and blinking to restore homeostasis and maintain ocular comfort.

For anyone interested in the tear film and DED, one of the best resources, for me, has been the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society (TFOS). This global group of more than 100 experts on DED defines what DED is, and how to diagnose and treat it. In my opinion, it is well worth joining and reading the TFOS Dry Eye Workshop reports, which analyse all the scientific evidence surrounding this subject in extraordinary detail.

Dry eye affects patients in a number of different ways

The TFOS DEWS II report noted that DED was characterised by loss of tear volume, more rapid break-up of the tear film and increased evaporation of tears from the ocular surface. The tear film lipids, proteins, mucins and electrolytes contribute to the integrity of the tear film – but exactly how they interact is still an area of active research.

Affects of DED on our patients

That’s the scientific definition of DED, but what does it actually mean to our patients? What is the effect of DED on the person? How does it affect their day-to-day life? Does it affect their Quality of Life (QoL)?

Several scientific papers demonstrate that DED significantly affects the lives of sufferers. One report1 indicated that it has the same negative QoL score as angina sufferers. DED impacts the physical, psychological and emotional well-being of our patients, influencing overall and mental health, social functioning and vitality, which decline further in cases of more severe disease2.

The impact that DED has on the individual who came in to see you should never be underestimated:

- “I don’t feel that I’ve been taken seriously”

- “They said it’s just dry eye, use some drops”

- “No-one takes time to listen”

- “It’s bringing me down, I feel so depressed”

- “It wakes me up at night”

These are all statements that I’ve heard in my dry eye clinic over the years. One of the most important things that you can do with any patient, but especially your dry eye patients, is to listen.

After all, it’s the first in the list of standards of practice issued by the General Optical Council – “Listen to patients and ensure they are at the heart of the decisions made about their care”.

References

1. Schiffman RM, Walt JG, Jacobsen G, Doyle JJ, Lebovics G, Sumner W. Utility assessment among patients with dry eye disease. Ophthalmology 2003;110(7):1412-9.

2. Uchino, M and Schaumberg DA. Dry eye disease: impact on quality of life and vision. Current Ophthalmology Reports 2013;1(2):51-57.

Next month, Keith will look at published results from a Social Media Listening research paper into patient experiences of DED and its effects.

Keith Tempany FBDO CL FBCLA qualified in 1976 and worked in both independent and multiple practice before opening a fee-based contact lens only practice in 2002. He is a fellow and a past president of the British Contact Lens Association (BCLA) and oversaw the development and launch of its Myopia Management Certificate. Keith is the store director of Leightons & Tempany Opticians & Hearing Care in Poole, and works as an independent consultant. He is an experienced author, lecturer and facilitator of contact lens and dry eye education both nationally and internationally.