OA Corner Part 11: Understanding glaucoma

In this month’s OA Corner, we look at glaucoma, tonometry and visual field screening.

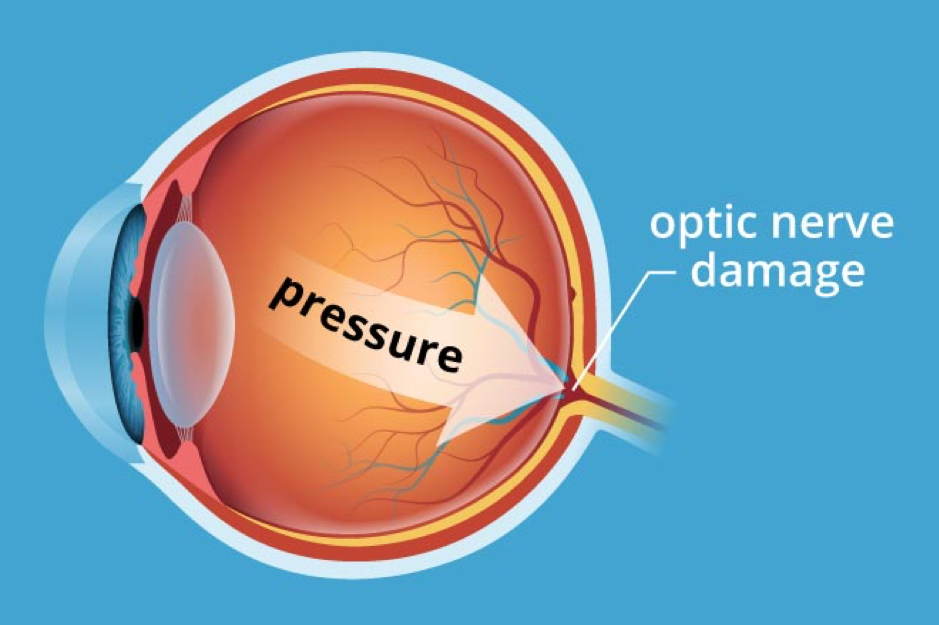

Increased intraocular pressure can damage the optic nerve

What exactly is glaucoma? Well, this is not an easy question to answer but it is one that most OAs will be asked from time to time. It is important to stress that glaucoma is not simply raised intraocular pressure (IOP) and measurement of IOP using a tonometer is not a standalone test for glaucoma.

There are many different types of glaucoma – but essentially glaucoma is a group of diseases that result in changes to the optic nerve head at the back of the eye along with a loss of retinal cells. These changes can result in progressive and permanent visual field defects and potentially blindness.

IOP is no longer included in modern definitions of glaucoma. However, a raised IOP is the major and only modifiable risk factor in glaucoma. Increasing age, a family history of glaucoma and certain ethnic backgrounds are also risk factors for glaucoma.

Open and closed angle glaucoma

The pressure within the eye is a result of the aqueous humour, which is a clear fluid secreted by the ciliary body. This fluid circulates around the anterior and posterior chambers of the eye, and flows between the angle formed by the iris and the cornea before passing through the trabeculae meshwork.

The IOP at any one time is a balance between the production and drainage of aqueous. If too much is produced, the IOP may rise or if there is a problem with drainage the IOP may also rise.

In chronic open angle glaucoma (COAG), the angle between the iris and cornea is open and the aqueous can pass through to the trabeculae meshwork. Patients with COAG are usually asymptomatic in the early stages of the disease.

One variety of COAG is normal tension glaucoma (NTG). This is when glaucoma has been diagnosed but the IOPs at the time of diagnosis are within the normal range. In other words, not raised. Damage to the optic nerve is therefore not a result of a raised IOP and, in most cases, has a vascular cause.

Angle closure is an ocular emergency and the patient will usually present with acute symptoms. This occurs when the angle between the iris and the cornea closes and so the aqueous is unable to flow, which results in a sudden rise in pressure. This can be very painful and can even induce vomiting. Other symptoms include a red eye, headache, blurred vision and haloes around lights. If this is not treated urgently, sight loss can occur.

Measuring IOPs with tonometry

The measuring of IOP as part of a routine eye examination in patients over the age of 40 is primarily to collect baseline information, which can be referred to in future examinations and also to identify those patients with a raised IOP at the time of the examination. As previously mentioned, a raised IOP is a major risk factor for glaucoma. However, it is important to stress that this is not a test for glaucoma.

IOP is measured using an instrument called a tonometer. Normal IOPs range from 10-21mmHg with 16mmHg considered average. Ocular hypertension (OHT) is when the IOP is consistently > 21mmHg in the absence of optic nerve damage or a visual field defect.

The treatment threshold for OHT is now 24mmHg (NICE 2017) and patients with an IOP of 24mmHg or more can be referred routinely via their GP or by means of a referral pathway. It should also be remembered that patients can have COAG at any level of IOP including very low values. IOP reduction is achieved by the use of eye drops or surgery.

Visual field screening

The OA will sometimes be asked to perform visual field screening as part of glaucoma case finding. Field screeners, such as the Henson or the Humphrey visual field screener, can be used to detect areas of reduced sensitivity in the visual field. Various spots of light known as stimuli are presented to the patient.

Some test programmes determine the exact ‘threshold’ at each point presented to the patient. The threshold is determined by increasing and reducing the intensity of an individual spot of light until the patient can see it 50 per cent of the time, and miss it 50 per cent of the time.

These full threshold tests are time consuming and can be stressful for the patient. As the results are compared with a normative database, full threshold tests are often used for confirmation of diagnosis and the monitoring of patients with confirmed glaucoma.

An alternative test is the suprathreshold test. Here, the intensity of the individual stimuli is based on the patients age and are adjusted so that they are just brighter than what the patient should be able to see. Younger patients can detect dimmer lights than older patients, who may require the test points to be significantly brighter.

In suprathreshold tests, all the stimuli are the same brightness. Suprathreshold tests are useful for screening purposes as they are quicker and therefore less stressful than full threshold tests. Both full and suprathreshold tests make use of the patient’s age – so it is important to enter the patient’s age correctly.

OA Corner Part 1: What makes a good OA

OA Corner Part 2: Communications

OA Corner Part 3: A question of strategies

OA Corner Part 4: Understanding bifocals

OA Corner Part 5: Our amazing eyes

OA Corner Part 6: Frame fittings basics

OA Corner Part 7: Frame styling factors

OA Corner Part 8: Single vision lens basics

OA Corner Part 9: Explaining spectacle prescriptions Part 1

OA Corner Part 10: Explaining spectacle prescriptions Part 2